On Saturday I woke up and realized I was behind in Middlemarch.

I have been reading Middlemarch because our daughter is writing about it.

Years ago, my wife, who is an English teacher and a whole human being in her own right, as they say, read it also. It took a long time; it is a long book. She really had to concentrate.

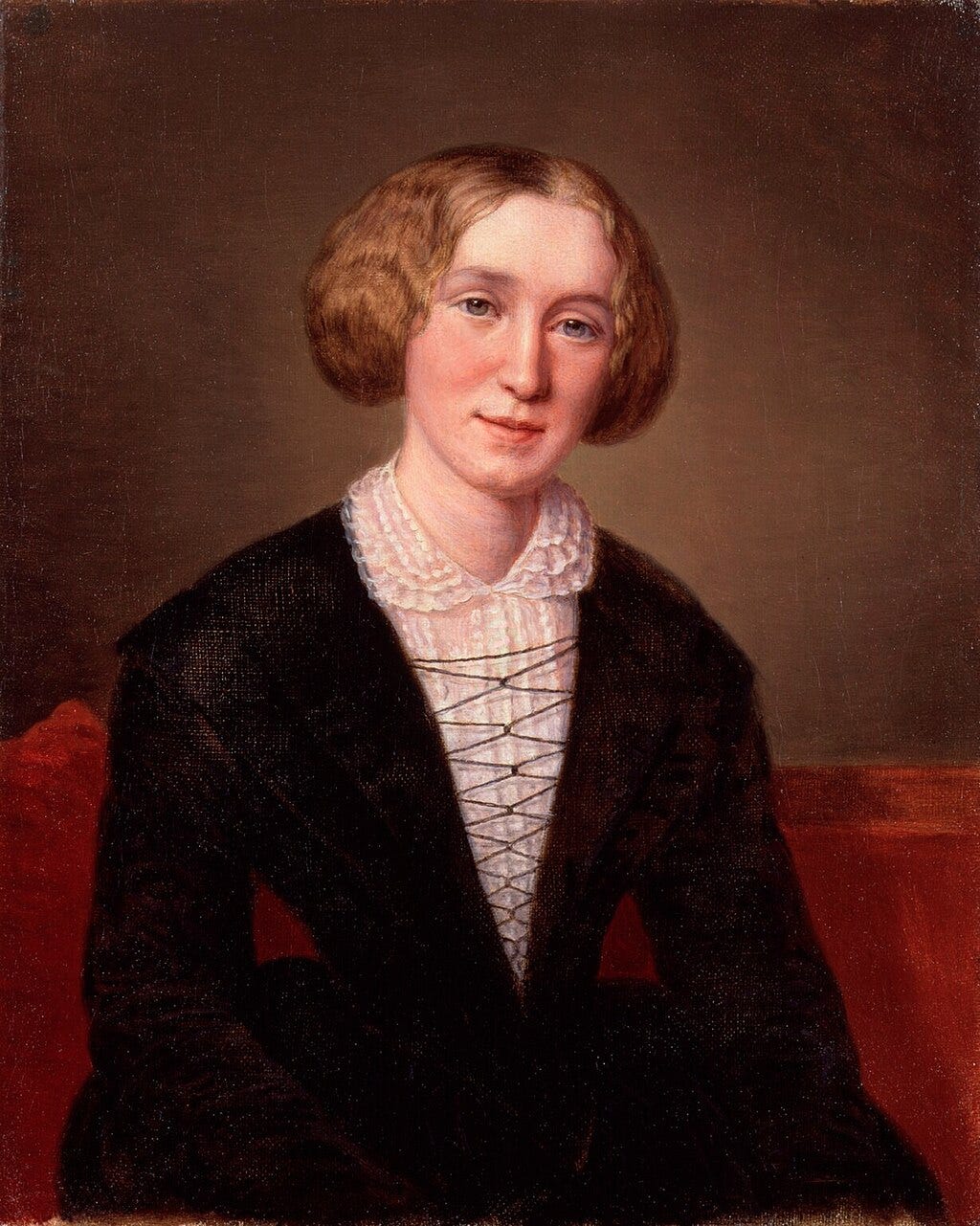

George Eliot wrote it it in the early 1870s, and sentences were different then. Long, with lots of commas. Full of subtleties and lots of presumed knowledge about mythology, the social life of the English Midlands in the 19th century, and the reform act of 1832.

According to my wife, each sentence was its own little novel to puzzle out. That sounded really boring to me.

Probably I was reading nothing at the time. If anything I was consuming Parker novels like potato chips. The PARKER novels, about a professional thief called Parker, were written by Donald Westlake under the pen name Richard Stark.

Westlake’s sentences are blunt and plain. Only later did I understand that was because he was writing from Parker’s point of view, and Parker is also blunt and plain.

There is one scene in one of the books (I’m not going to look it up; if you haven’t guessed already, I’m lazy), in which Parker has arrived in some town to steal some thing.

He has to wait til midnight or whatever to go out to do the stealing, so with nothing else to do, he sits in the dark in his hotel room and stares at the wall.

But: after a while, there’s a knock on the door—someone Parker wasn’t expecting. (This is the excitement of fiction: things happen*).

Parker gets up and turns the light on. And Westlake writes, something like: “Parker turned the lights on before answering the door. He had learned that people thought it was strange when he sat alone in the dark.”

Again: I’m not quoting here. Because: lazy. That was the gist. But I had my own illumination when Parker turned the lights on, which is Westlake is writing this way on purpose. He’s writing short and blunt because that’s how Parker processes the world.

He doesn’t experience emotion the way normals do. And he knows it.

Reading book after book of Parker at this time was a real tonic. It was not long after a certain election, and it felt good to inhabit a person without emotion at that time.

(Later, both Westlake and Parker would undermine this exquisite distraction when, in one of the last Parker books, he goes to Palm Beach and talks about the new owner of Mar A Lago. Betrayal is another thing that happens in stories*).

And sometimes Westlake would take a chapter told from the point of view of one of Parker’s fellow crooks, Alan Grofield. Grofield has plenty of emotions: when he’s not a burglar, he’s an actor, and a lady’s man, and when he’s the POV character the language all turns all suave and dandy.

So Westlake is a really good writer, but even at his best his sentences were not whole novels. In many cases, his novels went down as easy as short sentences, made out of, as I say, potato chips.

And that’s why Middlemarch seemed like a lot of work when my wife was reading it, even though she really ended up loving it, and I made a quiet agreement with myself not to ever fuck with it.

But then years later our daughter took up Middlemarch and LOVED it. Read it twice. Easy peasy. And made it the center of her college work.

So now I felt like a real dope. And as the new year started, I decided I should honor these two smart people in my life and give it a try.

My efforts were very modest. I would read one percent of it a day—about a chapter or a little less, depending. And then I would go back and read LEGION OF SUPER-HEROES comics from the 90s and/or mix it up with the malcontents in the Maine subreddit as usual.

But as I got along into it, I realized: George Eliot is really funny. It’s absolutely true that the sentences are complex, but they are lovely to puzzle out. And it makes it easier if you read them out loud and half-way channel Carrie Coon in GILDED AGE (my new one person show, maybe?)

Eliot was groundbreaking in her understanding of human psychology, he sympathy for all of her characters, her ability to capture and crystallize whole worlds in a moment.

One famous observation from Middlemarch came up in my reading on Saturday and it is this:

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.”

And it’s not hard to guess George Eliot is talking about herself. That’s her, hearing all those squirrels’ hearts beating, so keen is her observation, and her suffering of same. No wonder the sentences are long!

But if you’ve been following my instagram on this subject, you will also get a sense of the plain haha of Eliot, her capacity to be sly and withering, acid and hilarious.

I won’t tell you the story of Middlemarch. You should read it.

But part of it involves a young man named Will Ladislaw, who has become infatuated with his cousin-by-marriage Dorothea Brooke, a young idealist who marries an older man that she thinks is a brilliant scholar, but who, it is no spoiler to say, turns out to be a real mediocre drip.

As Eliot writes..

“But the idea of this dried-up pedant, this elaborator of small explanations about as important as the surplus stock of false antiquities kept in a vendor’s back chamber, having first got this adorable young creature to marry him, and then passing his honeymoon away from her, groping after his mouldy futilities (Will was given to hyperbole)— this sudden picture stirred him with a sort of comic disgust.”

That’s a very long sentence! And every clause of it: FATALITY.

Anyway, as I was posting these quotes to insta, a nice stranger pointed out that my old friend Christopher Frizelle of Seattle was, at this very moment, HOSTING AN ONLINE MIDDLEMARCH BOOK CLUB.

I hadn’t spoken to Chris in years. What serendipity! This is like something that might happen in fiction*. So I joined the group, and on Saturday morning I woke up and I attended my first session.

(But first, I had to catch up with the group. For all my percentages of Middlemarch I had read, I was a few percentage points behind).

And it was a god or whatever damned delight. Chris is an amazing discussion leader, and everyone was so thoughtful and smart. It was a really nice way to pass an early spring midday with the windows open to the chill and the promise.

Much better than than reddit or any of my other mouldy futilities.

Each week Chris opens the discussion by asking everyone to choose a passage to read aloud, what he calls A SYMPHONY OF SENTENCES, and you can hear all of those little novels right now on his substack HERE.

And here is a little preview (I’m not in this one, as it’s from the other week)

I’m not saying the group makes Middlemarch easy. Indeed, we ended the session on a pack of sentences that was a real stumper. Maybe you can make sense of it…

“The world has been too strong for ME, I know,” [Vicar Farebrother] said one day to Lydgate. “But then I am not a mighty man — I shall never be a man of renown. The choice of Hercules is a pretty fable; but Prodicus makes it easy work for the hero, as if the first resolves were enough. Another story says that he came to hold the distaff, and at last wore the Nessus shirt. I suppose one good resolve might keep a man right if everybody else’s resolve helped him.”

WHAT ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT GEORGE? Let me know if you know.

But being confused in good company is also a good time.

It’s obvious to you by now that I don’t know where I’m going these days, creatively. Writing feels less intuitive than it used to. Inspiration comes more slowly. Sometimes I hear every squirrel’s beating heart. Often I hear nothing.

(*I even had to start making a LIST OF THINGS THAT CAN HAPPEN IN A STORY. That’s how basic I’ve become. Maybe next week I’ll read it to you.)

But as in Chris’s Middlemarch group, trying new and even daunting things, and having you here to be confused with is both motivating and consoling.

I don’t know if I’m going to be able to join the group again this Saturday, or even next (as you see, I will be AT SEA), but trust me, there is a LOT of Middlemarch left, and so I will be coming back. And maybe I will see you there.

In the meantime, I’m leaving a little SECRET MESSAGE at the top of the stairs—a little further exploration of serendipity in the world of happiness expert, trained archeologist, and thesauran Babara Ann Kipfer.

But to all of you: thank you for the company and kind attention. That is all.